The British Régime in Wisconsin and the Northwest: Chapter 20

XX. Prairie du Chien and the Treaty of Peace, 1814–1815

The importance of Prairie du Chien for the British fur trade was apparent from the time this settlement passed from French to English sovereignty. We have also seen that, although within American territory after 1783, it had been controlled in the interests of the fur trade by British subjects. Several attempts were made to draw a new international boundary, which would exclude this important post from American territory and would perpetuate British control over this rich fur bearing region. The close of the War of 1812 seemed to offer an opportunity to redraw this boundary and to obtain this valuable fur trading region for the British crown.1

In anticipation of some such settlement the Americans determined in the spring of 1814 to secure possession of Prairie du Chien and fortify it against British forces, now concentrating at the post of Mackinac. At the very time when Dickson and his hordes were leaving Prairie du Chien for that place, William Clark, governor of Missouri territory, was enrolling troops to advance up the Mississippi with Prairie du Chien as his objective. On the first of May, five barges left St. Louis loaded with sixty-one regulars and about one hundred and forty volunteers, all under the immediate command of General Clark himself. Two of the barges were fitted up as gunboats, the larger of which, named the General Clark, was commanded by Captain Frederick Yeiser of the St. Louis militia.2 On board of this gunboat were the regulars, most of whom were from the Seventh United States infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Joseph Perkins of the Twenty-fourth.3

The first opposition to its advance occurred when the warlike flotilla arrived at Rock island. There the hostile Sauk fired upon the boats and after vigorous action on the part of the Americans, the frightened Indians sued for peace. This was granted them on condition that they would take up arms against the enemy Indians, the Potawatomi and Winnebago. At the Dubuque mines the Foxes obtained the same terms.4

The flotilla arrived at the Prairie June 2, only to find that the few militia under Captain Dease, that Dickson had left for the protection of this place, had run away on hearing of the approach of the Americans. On landing, the troops took possession of the warehouse of the Michilimackinac company until a fort could be built. Clark chose as the site a small mound back of the village and one of the most commanding spots.5 Perkins began the building of the fort the sixth of June, and the next day, after giving the new post the name of Fort Shelby6 in honor of the governor of Kentucky, Clark and a few friends who had accompanied him returned down the river to St. Louis. Clark took off with him three of the boats leaving the two gunboats to protect the new post from the riverside. He also carried away nine or ten trunkfuls of Dickson's property, among which were two containing the papers he had left at Prairie du Chien—'a grand prize.'7

The building of Fort Shelby proceeded apace. On June 19 the troops moved into it and mounted a six pounder in one blockhouse and a three pounder in the opposite one.8 The United States flag was now raised over the fort, the first flag of that nation, so far as is known, to fly over any building in what is now Wisconsin.9 The fort was a substantial structure surrounded by stout oak pickets ten feet high; within the enclosure were log huts to house the troops. A chevaux-de-frise ran to the river to keep open communication with the gunboats.10 The troops were considered good average soldiers; Lieutenant Perkins was supported by James and George Kennerly of St. Louis, who served as his staff aids and were militia officers with the rank of captain and lieutenant respectively.11 The detachment was composed of fifty-four privates, one fifer, three corporals, and two sergeants—one each of the Seventh and Twenty-fourth regulars.12 On the gunboats were one hundred and thirty-five volunteers, whom Clark designated as 'dauntless young fellows from this county.' He reported after his return that the farms about Prairie du Chien were in a high state of cultivation, and that from two to three hundred barrels of flour could be made that year. Horses and cattle were abundant. He augured well for the safety and support of the garrison at Fort Shelby, which he thought 'more important to these territories than any hitherto undertaken.'13

The last of June the smaller gunboat, commanded by Captain John Sullivan, slipped its moorings and returned down the river with the volunteers whose sixty-day term had expired. Sullivan reported that Fort Shelby was completed and was one of the strongest fortifications on the western waters. The Governor Clark gunboat, still opposite the fort, had a six pounder on her main deck and a three pounder and ten howitzers on her quarters and gangway. 'The regulars,' he wrote, 'are all anxious for a visit from Dickson and his red troops.'14

The garrison of Fort Shelby all too soon had its desires granted. Not only Dickson's Indians, but British officers and soldiers were preparing to expel these American intruders from territory so long held by foreign fur traders. News of the arrival of the Americans at Prairie du Chien reached Mackinac June 21 at the very time when preparations were being made to resist an attack there by an American flotilla. Colonel McDouall at once saw that if the Americans should retain their hold on Prairie du Chien, the British influence with the Indians everywhere throughout the Northwest would be greatly impaired. 'A greater part of my Indian Force,' he wrote, 'was from the countries adjoining La prairie des Chiens, they felt themselves not a little uneasy at the proximity of the enemy to their defenceless families, but on the arrival next day of the Susell or tete de Chien, a distinguished Chief of the Winebago Nation (who came to supplicate assistance) & on his mentioning the circumstances of its Capture, particularly the deliberate & barbarous murder of seven Men of his own Nation, the sentiment of indignation & desire for revenge was universal amongst them.'15

Notwithstanding his own danger, Colonel McDouall decided to send off a force to retake Prairie du Chien. After consultation with Dickson, who remained at Mackinac, it was thought that the Sioux and the Winnebago could best be spared. The fur traders, Joseph Rolette and Thomas G. Anderson, were called in and given captains' commissions to raise troops among the voyageurs who were loafing idly around the fort. They raised sixty-three volunteers in a very short time.16 Pierre Grignon, who was also at Mackinac, was made a captain and sent to raise 'all the settlers of Green Bay.' The eager Indians asked for a big gun, and McDouall allowed them to take a three pounder with James Keating, a gunner of the Royal artillery. William McKay, an old Nor' wester, was commissioned lieutenant-colonel in command of the entire expedition.

With seventy-five white volunteers and one hundred and thirty-six Indians, McKay sailed from Mackinac June 28 and six days later arrived at Green Bay.17 The historic July 4 was employed at this settlement in preparations to advance against the American outpost at the other end of the Fox-Wisconsin waterway. Captain Grignon enlisted a militia company of about thirty, many of them elderly voyageurs retired from service and somewhat unfit for the campaign. Augustin Grignon and Peter Powell were commissioned lieutenants, while the younger Jacques Portlier took a commission in the regiment called the Michigan Fencibles. About a hundred Indians were here enrolled—Menominee and Chippewa. The expedition moved up Fox river in six large barges with many accompanying Indian canoes. At the portage other Winnebago joined them18 McKay, while descending the Wisconsin, listed his forces and found he had an army of six hundred and fifty, of whom only one hundred and twenty were white men—'the remainder were Indians that proved to be perfectly useless.'19

As the expedition was moving down the Wisconsin, McKay sent scouts to observe the situation and to bring to him a citizen from Prairie du Chien. They landed where the ferry later crossed and going overland obtained the services of Antoine Brisbois, who reported that the American garrison was about sixty in number. McKay then went on to the mouth of the Wisconsin and up the Mississippi, landing without being perceived by the Americans. It Was Sunday, July 17, and the officers from the fort were preparing to take a pleasure ride into the country. Perkins said, 'a large body of British and Indians appeared in the prairie about 3 miles distant.' Boilvin was notified and hastened to go on board the gunboat for safety. The British advanced, flags flying, officers in red coats, making in the eyes of the astonished Americans a formidable display. Colonel McKay sent Captain Anderson to demand the fort's surrender, which Captain Perkins answered as became him, that he was 'determined to defend to the last man.'20 McKay then turned to the Governor Clark anchored in the stream opposite the fort and with his tiny cannon did considerable execution. Yeiser, feeling his position untenable, cut his cable and slipped down the river, leaving the garrison in the fort to its fate.

This fate seemed a desperate one, the gunboat had gone, ammunition ran low, the well caved in and there was no water, while all around the hordes of Indians yelped, fired, and were intent on massacre. Five soldiers within the fort were wounded, and there were no hospital stores. Perkins and the Kennerlys decided to appeal to the mercy of the British officers, and the appeal was not in vain. Late on the nineteenth a flag of truce was sent out and accepted by Colonel McKay. For safety from the Indians he requested the garrison to remain in the fort until the next morning, When they marched out with the honors of war.21

With great difficulty, McKay controlled his fierce Indian allies; the villagers, supposed to be their friends, suffered more at their hands than the American garrison. Although a plot was formed by the Winnebago to murder the unarmed soldiers, McKay and his aids guarded the Americans with assiduous care, and after a day or two placed them and provisions onboard one of his own boats, when after giving their parole they were allowed to return to St. Louis.

McKay's conduct at the capture of Fort Shelby greatly redounds to his credit, as a soldier and a Briton. The preparations, however, which he made to capture the fleeing gunboat led to a sanguinary battle at the Rock rapids. As soon as the gunboat had gone off, he sent some Indian runners with kegs of gunpowder and orders to raise the Sauk at Rock rapids, where he expected the large boat would ground. Meanwhile General Howard, all unaware of the fate of the garrison of Fort Shelby, had sent Major John Campbell of the First United States infantry with thirty-three regulars and sixty-six rangers in three keel boats to mount the Mississippi and relieve Captain Perkins.22 The rangers were commanded by Lieutenants Jonathan Riggs and Stephen Rector. July 21 as the expedition attempted to pass the rapids above Rock river, Campbell's boat grounded, and the Sauk Indians attacked and set the boat on fire. Rector, who was in advance, fell down and took out the survivors, losing several men himself. Riggs's boat was also disabled, drifted down, and its men fought Indians until dark. After the battle was over, Yeiser appeared in the Governor Clark, but apparently took no part in the conflict. The regulars suffered severely, losing eight privates and two sergeants in the fierce fire and the constant play of the savages' rifles during two hours and a half. Major Campbell and Dr. Stuart were severely wounded. The next day the boats were permitted to get off and return to St. Louis.23 Lieutenant Perkins was later allowed to pass without molestation, and reached the American settlement safely on August 6.

While all these contests on the Mississippi were occurring preparations were making for the defense of the island fort of Mackinac. The capture of this post at the outbreak of the war had made possible the British hold upon the Northwest, had given protection for the fur trade, and had held the upper lakes for the Canadian interest. Even after Detroit was retaken by the Americans, the possession of Mackinac had safeguarded the British on the upper lakes and permitted a million dollars worth of the North West company's furs to go down as a consignment to the agents at Montreal.24 The commander-in-chief of the British forces in Canada recognizing the importance of Mackinac sent there in the spring of 1814 a considerable garrison under Colonel Robert McDouall, a Scotchman of the Glengarry infantry.25 The reinforcements arrived the latter part of May at the Toronto portage, whence the schooner Nancy brought them to the island from Nottawasaga bay. Not long afterwards Dickson came from the West with his Indian forces, and the post was rapidly put in a state of defense.26 Fort George was built on the highest point of the island and made a strong fortress.

Meanwhile, at Detroit arrangements were going forward to capture this desired post. A considerable armament was prepared with several vessels, regulars, militia, and sailors, all under the command of Colonel George Croghan, the hero of Sandusky. With him went as second in command, Major Andrew Hunter Holmes of an eminent southern family.27 Croghan was not eager for the undertaking. He wrote his father July 3, from Detroit: 'My Troops are all on board the vessels of the squadron, & by daylight in the morning we will set sail for the Upper Lakes. My hopes are not very sanguine, the troops under my Comd are it is true picked, well disciplined fellows, yet if resistance [is] made by the Enemy [I fear] it will prove too stout for my handfull of 800.'28

And so it proved. The fleet arrived off Mackinac island, July 26, after sacking the North West company's storehouse at Sault Ste Marie. After several days of reconnoitering a landing was made in force on the western side of the island, at the very spot chosen by the British two years earlier. McDouall, who had fewer men than the Americans, awaited them behind a barricade with the Indians protecting his flanks. He especially relied upon the Menominee under their chief Tomah, and as the invaders attempted to deploy to the right of the British position the red warriors fired a fatal volley, killing Major Holmes at the first instant, wounding several officers and men, and throwing the whole American contingent into such confusion that Croghan was forced to retreat to his ships.29 Two Menominee always claimed the honor of having shot Major Holmes—L'Espagnol and Yellow Dog.30

After the departure from the island of the American squadron, a patrol was kept up on Lake Huron, hoping to intercept supplies for Fort Mackinac coming from Georgian bay. Two American vessels, the Scorpion and the Tigress, employed in that service were captured by a detachment from Mackinac as they lay at anchor off St. Joseph island. In this capture Dickson took a conspicuous part.

The American fiasco at Mackinac on August 4 and the subsequent capture of the two sailing vessels were loudly heralded by the British as considerable victories. The failure to take Mackinac confirmed for another twelvemonth the grasp of the British upon the entire Northwest.

The indignities suffered by the Americans in the battle at Rock river inspired at St. Louis an attempt to punish the Indians on the Mississippi, and if possible to move up the river and recapture Fort McKay. Perkins reported that the British garrison was small and that the Indians had begun before he left to slip away to their villages. An expedition was prepared under the command of a regular army officer, Major Zachary Taylor, who two years earlier had distinguished himself in the defense of Fort Harrison. Besides the troops stationed near St. Louis, a considerable force of militia and rangers was enrolled in Illinois commanded by Samuel Whiteside; with him was Captain Nelson Rector, brother of the officer concerned in Campbell's defeat.31 Taylor had over three hundred troops in eight barges, and was supplied with several small cannon; his boat bore a white flag at its masthead in token that he came in peace. This was changed to a red flag, meaning 'no quarter,' after the Indians attacked.32

News of the approach of` this armament reached Fort McKay in due season. The officer of that name had returned to Mackinac leaving Captain Thomas Anderson in command. Anderson did not dare leave his post exposed to the fickleness of his Indian allies; he, thereupon, sent a Scotch trader, Duncan Graham, with a few companions and two cannon taken from the Americans, to hold the rapids and repel the oncoming expedition. Anderson trusted largely to the aid of the Sauk Indians whose chief, Black Hawk, had acted efficiently in Campbell's repulse.33 Nevertheless, to supplement their efforts he employed fifty Sioux under Wabashaw, some Foxes and Winnebago, making in all a force of about eight hundred savages.34

It was a forlorn hope, a motley band of savages with a few white leaders and two small guns against a well-equipped force from the American settlements. Graham hoped only to delay the expedition for a short time. He planted his two big guns so as to rake the river and added several painted guns of logs to make the effect of a large battery. He wrote: 'We are determined to dispute the road with them inch by inch.'36

Taylor reached the Rock rapids on September 4 and was unable to pass them because of low water and heavy head winds. His fleet anchored for the night. All was quiet, there was no hint of the eager savage foe until daybreak when one sentinel was killed. At daylight on the fifth the attack began; Taylor's boat was raked by the British cannon. A large band of Indians hastened over to Credit island at the west; the boats were between two fires. Rector and Whiteside dropped below to get out of the range of the enemies' guns; Taylor's boat followed theirs. The British dragged their guns along the bank and continued to fire; of the fifty-four shots all but two or three did execution on the boats. Eleven men were wounded of whom three died. Prudence seemed the essence of valor. The expedition returned down stream, leaving victory to the Indians and the few British militia. Graham praised the fidelity of Lieutenants Michael Brisbois and Colin Campbell, both half-breed Indian traders. Sergeant James Keating, the gunner, was the hero of the hour.37

This was the last American attempt to invade Wisconsin and wrest it from the control of the British while the war lasted. Prairie du Chien was guarded by a British garrison until May, 1815. Lieutenant Anderson was replaced by Captain Andrew H. Bulger of the Royal Newfoundland regiment. He ruled the traders and tribesmen with a heavy hand, and in the spring of 1815 caused the arrest and disgrace of Robert Dickson.38 News of the signing of the treaty of peace reached Prairie du Chien from St. Louis, whence the gunboat General Clark was sent up the river, this time on an errand of peace, to announce the cessation of hostilities. This news was most unwelcome to the Indians, who had been promised protection by the British, and who now realized that they had been betrayed into the hands of their enemies. So great was the dissatisfaction and turbulence that Bulger feared his troops would be attacked if he withdrew from Fort McKay.

Orders came from Mackinac May 20 for immediate evacuation of the post. Bulger called Chief Black Hawk to his aid and held a great peace ceremony in the council house, wherein the chiefs, after much parleying, accepted the pipe of peace. Thereupon Bulger and his troops quickly retired to Mackinac.39 This latter post was transferred July 15 to a detachment of American riflemen under Colonel Anthony Butler, who renamed Fort George, Fort Holmes, in honor of the officer who fell in the attack of the previous year.40 With the evacuation of Fort McKay and the surrender of Fort Mackinac, the British control of Wisconsin ceased. What the Americans could not accomplish by force of arms, their diplomats obtained during the negotiations at Ghent.

Upon the first exchange of terms leading to a peace, the British ministry insisted as a sine qua non upon an change of boundary which would retain the western posts, and the erection of a neutral Indian state west of the Great Lakes. The American commissioners refused to consider such a condition of peace; John Quincy Adams thought it probable that the negotiations would end at this point and prepared to leave for home. When the news of this part of the negotiations reached Canada, the officers there told the Indians that the war was being prolonged for their sake.

But the British ministers wanted peace, the Napoleonic wars were ending, the desire for peace was strong. They, thereupon, determined to abandon their Indian allies and withdraw the demand for a neutral Indian state. Boundaries drawn on the basis of uti possedetis was the next provision offered. Had this been accepted by the United States envoys that nation would have gained a part of Upper Canada, but would have lost all of what is now Wisconsin. Again the negotiations halted on this new proposal, when the Duke of Wellington came to the aid of the Americans by declaring the nuti possedetis an untenable basis for peace.41

November 10, 1914, the American envoys offered the status ante bellum as a solution of the boundary and Indian problems. The British agreed, and the following article was drawn: 'The United States of America engage to put an end, immediately after the ratification of the present treaty, to hostilities with all the tribes or nations of Indians with whom they may be at war at the time of such ratification, and forthwith to restore to such tribes or nations respectively all the possessions, rights and privileges they may have enjoyed or been entitled to in 1811.'42 Thus the United States claimed and accepted full sovereignty over the tribesmen within its borders. This being the crucial problem of the treaty, other matters were quickly adjusted, and the whole was signed December 24, which Commissioner Adams declared was the happiest day of his life.43 Well he might so declare, for the American envoys had won a notable victory for their nation.

The British officers in Canada were much displeased with the result of the negotiations. Colonel McDouall wrote from Mackinac to Captain Bulger at Prairie du Chien: 'Our negotiators, as usual, have been egregiously duped: as usual, they have shown themselves profoundly ignorant of the concerns of this part of the Empire. I am penetrated with grief by the restoration of this fine Island—"a fortress built by nature for herself"—I am equally mortified at giving up Fort McKay to the Americans.'44

The treaty of Ghent was the last of the diplomatic series which concerned the British régime in Wisconsin. Four times during this period had Wisconsin been a pawn in the game of the diplomats during international treaties: first, when France in 1763 with deep reluctance ceded this hinterland of her American empire to her British rival. Again, in 1783 Wisconsin was vitally concerned in the extent of territory obtained by the United States envoys from the British government. Thirteen years later Jay's treaty between England and the United States freed Wisconsin from the military dominance of British garrisons. Finally, in 1814 the treaty at Ghent broke the monopoly of the British traders, and their control over Wisconsin Indians. It forever laid at rest the plan for a neutral Indian state, which would have condemned Wisconsin to remain a wilderness reserved for Indians and fur bearing animals exploited by traders for their own profit.

The American victory at Ghent ended the British régime and opened the way for Wisconsin to attain its destiny as the home of a free, liberty-loving people recruited from Europe and America. Long years were to pass before the Indian inhabitants ceded their rights of the soil to the United States government—years of turbulence and unrest, of military garrisons, and of pioneer undertakings in taming and redeeming the wilderness. Then in the fullness of time Wisconsin was admitted as a state in the federal union, a full partner in the sisterhood of states, yet still retaining some traces of its long history, of the days when it was a distant portion of the empires of France and Great Britain, when French voyageurs and Scotch bourgeois paddled their way through its waterways, and Wisconsin woods resounded to the songs of the boatmen and the moccasined tread of Indian hunters.

Throughout the British régime the small settlements at Green Bay and Prairie du Chien retained the character they had received during the former period.45 Although their allegiance was to the English sovereign, their habits and customs were those of the earlier day. The language employed in Wisconsin during the entire British régime was French, and the Scotch and foreign traders soon assimilated to type. At the Green Bay settlement Charles de Langlade remained the leading settler until his death at the beginning of the nineteenth century. This leadership was continued by his grandsons, the Grignon brothers, supplemented by their tutor and friend, Jacques Portlier. At Prairie du Chien the Brisbois family, the Gautiers, and Joseph Rolette maintained the French traditions. As the British traders departed with the garrisons, the French inhabitants resumed their former habits, and ultimately became American citizens, but alien in speech and customs. Thus the British régime of sixty-five years was an interlude in the process, called by an earlier historian of Wisconsin, 'the Americanization of a French settlement.'46 The British traders came and went, took their toll of Wisconsin's furs and enriched themselves at the Indians' expense. They built numbers of trading posts on the lakes and rivers of Wisconsin, but these were transitory. They developed no institutions, assumed no governmental functions, built up no new settlements. The British régime was a wilderness régime, perpetuated solely in the interests of the fur trade. Not until its close could civilization come to Wisconsin and here build a modern, American community.

1 Davidson, North West Company, appendix N.

2 Yeiser was a Kentuckian who in 1811 had a store in the village of St. Louis.

3 Perkins enlisted in 1812, was commissioned second lieutenant; he retired from the army in 1815 to enter the fur trade and was in 1819 a member of the Missouri fur company.

4 Draper MSS, 26S156.

5 Perkins' report is in adjutant general's office, Washington; designated 'old record.' A copy was furnished us by Dr. P. L. Scanlan, Prairie du Chien.

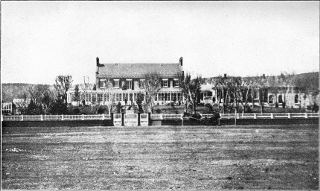

6 The site of Fort Shelby was an Indian mount not far from the Mississippi, now in the grounds of the Dousman residence, Prairie du Chien.

7 Draper MSS, 26S157; Wis. Hist. Colls., xii, 116.

8 Perkins' report, op. cit. The three pounder did effective service later; see Wis. Hist. Colls., ix, 296.

9 After correspondence with R. C. B. Thruston, author of The Origin and Evolution of the United States Flag (Washington 1916), it seems probable that this flag was the fifteen-star fifteen-stripe flag, then the official emblem. It may have been instead a regimental flag with the United States arms on a blue ground.

10 Wis. Hist. Colls., ix, 195.

11 For the Kennerly brothers see Mo. hist. soc. Colls., vi, 41–123.

12 The muster roll of the troops at Fort Shelby is from the adjutant general's office, Washington, 'old records.' After the capture the British claimed four as subjects, two of whom were deserters.

13 Draper MSS, 26S157–158.

14 Ibid., 159.

15 William Wood, editor, Select British Documents on the Canadian War of 1812 (Champlain society, Toronto, 1926), iii, 253. See also Wis. Hist. Colls., xi, 260, where the word printed 'Nov.' should be read 'ult.'; the American report of atrocities is ibid., 824.

16 Anderson's narrative is in Wis. Hist. Colls., ix, l93–201. It is very boastful and not entirely accurate; for lists of the volunteers see ibid., 262–265.

17 Ibid., xi, 260–263. Larger numbers are given in a journal of this expedition in Green Bay Historical Bulletin, i, No. 3. For sketch of McKay see Documents Relating to the North West Company, 474.

18 Wis. Hist. Colls., iii, 271–272. Grignon gives the names of the principal Indian leaders.

19 McKay's report in ibid., xi, 263–270.

20 Ibid., xi, 256.

21 Ibid., 257; McKay's report, 265; Perkins' report, op. cit.

22 Draper MSS, 26S163.

23 Wis. Hist. Colls., xi, 269–270; Draper MSS, 26S162–170. MS reports by Lieutenant Riggs and Major Campbell, from adjutant general's office, Washington, 'old records'; Life of Black Hawk, op. cit., 56–59.

24 Franchère's Narrative in Thwaites, Early Western Travels, vi, 297.

25 For a sketch of this officer see Wis. Hist. Colls., ix, 193.

26 Wood, Select British Documents, iii, 271–273.

27 Holmes was born in Virginia, went to Mississippi with his elder brother, Governor David Holmes. He enlisted in 1812, was commissioned captain and brevetted major for bravery at the battle of the Thames.

28 Unpublished letter, Draper MSS, 1N79.

29 McDouall's report, in Wood, Select British Documents, iii, 273–277.

30 Wis. Hist. Colls., iii, 270, 280; x, 499.

31 For these officers see John Reynolds, Pioneer History of Illinois Chicago, 1887), 353–354, 409.

32 Taylor's report is in Draper MSS, 26S178–183.

33 Wis. Hist. Colls., ix, 198; Life of Black Hawk, op. cit., 58–61.

34 See orders for Graham, Wis. Hist. Colls., ix, 219.

35 Ibid., ii, 220–222.

36 Ibid., ix, 226.

37 Graham's report, ibid., 226–228; also 284, 464.

38 Tohill, 'Robert Dickson,' 120–122; Wis. Hist. Colls., xi, 311.

39 Wis. Hist. Colls., xiii, 130, 150–151, 154–162.

40 Wood, Select British Documents, iii, 538–539.

41 Worthington C. Ford, editor, Writings of John Quincy Adams (New York, 1915), v, 179–180.

42 Wood, Select British Documents, iii, 524.

43 Ford, Writings of John Quincy Adams, v, 256.

44 Wis. Hist. Colls., xiii, 143.

45 Kellogg, French Régime, chap. xviii.

46 R. G. Thwaites, Wisconsin (New York, 1908).

![[Public Domain mark]](http://i.creativecommons.org/p/mark/1.0/88x31.png)